It's 2028. Building software is essentially free. So if you can build anything, why would anyone buy anything?

Imagine you decide to handle payments yourself. You describe what you need, routing, retry logic, error handling, and have a working version by afternoon. It passes your test suite, so you ship it. Then a Brazilian bank changes its fraud detection, and your retries start triggering false declines. You fix the retries, but the fix delays settlements past a regulatory deadline you didn't know about, freezing funds for hundreds of merchants. Each fix surfaces a problem you couldn't have specified in advance. You give up and pay Stripe.

You build your own clinical documentation tool. It transcribes perfectly. Then a payer changes its reimbursement codes and your documentation starts getting claims denied. The format of the note determined whether you got paid, and you didn't know that. You switch to Abridge.

You set up a threat detection system trained on every known attack pattern. In production, attackers adapt within hours. Every signature you publish teaches them what to avoid next. You call CrowdStrike.

In each case, you didn't fail at building. You failed at knowing. Not the code, but everything the code doesn't capture: the Brazilian settlement deadlines, the payer's documentation quirks, the attacker's next move. You paid these companies for everything they'd already learned by operating in a system that keeps changing. You paid for their scar tissue.

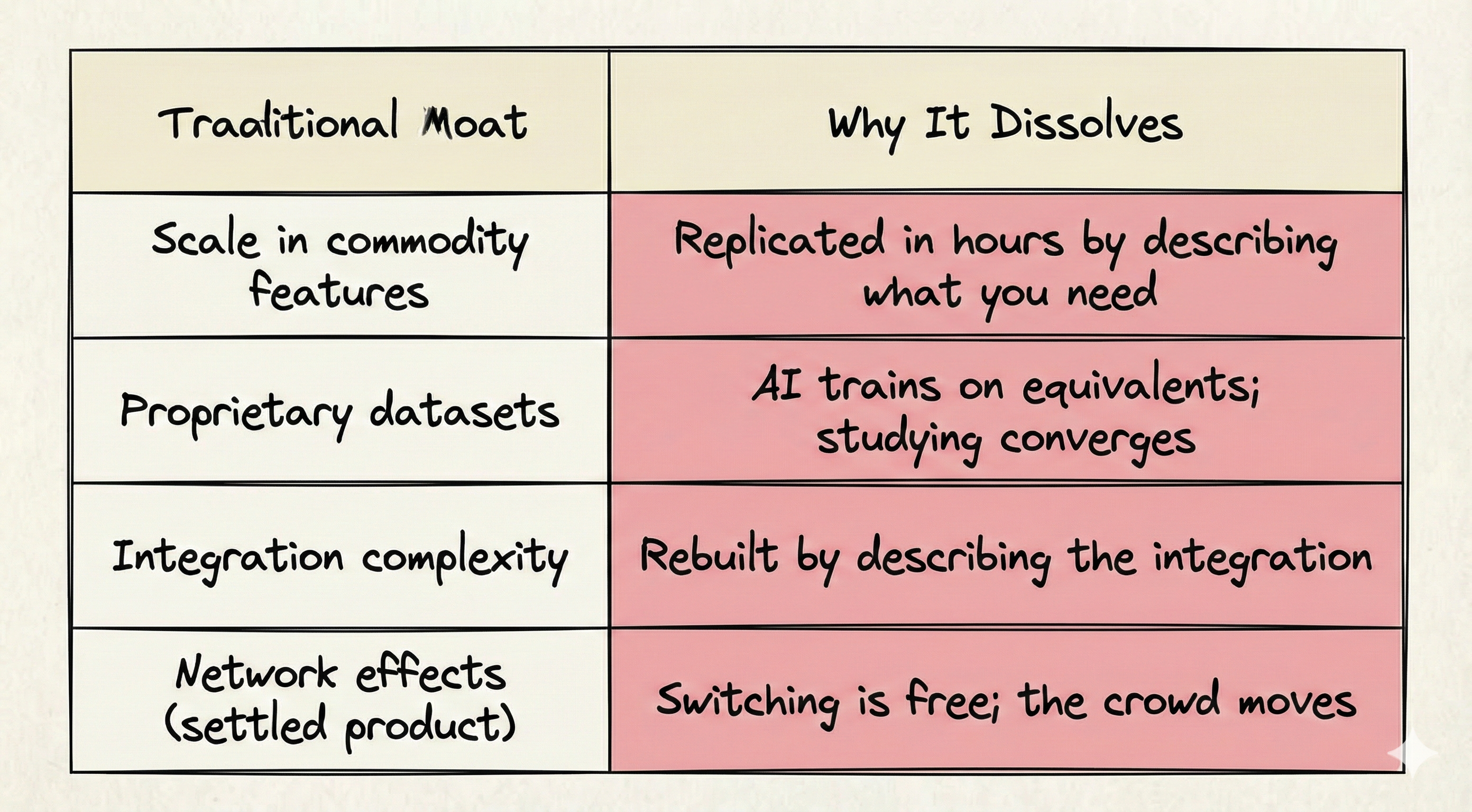

When building is free, most of what we call "moats" dissolve. Scale advantages in commodity features can be replicated in hours. Proprietary datasets built from recordings and logs lose their edge once AI can train on equivalents. Integration complexity gets rebuilt by describing what you need. Network effects around a settled product collapse when switching is free, because the crowd moves.

What survives isn't code; anyone can build that. And it isn't data you collected by watching, because anyone can study their way to the same conclusions. What survives is knowledge that could only have been learned by operating in a system that keeps changing. Scar tissue, earned one surprise at a time.

Every software product is really a ratio:

Scar tissue to specifiable code.

Every layer of a product sits somewhere on a gradient from fully specifiable to fundamentally unspecifiable. What you can specify, AI can build and anyone can learn by studying. What you can't specify, AI can't build and only operating reveals. When code goes to zero, only the unspecifiable knowledge is left. A company that was 90% operational knowledge barely notices. A company that was 90% specifiable code just lost its reason to exist.

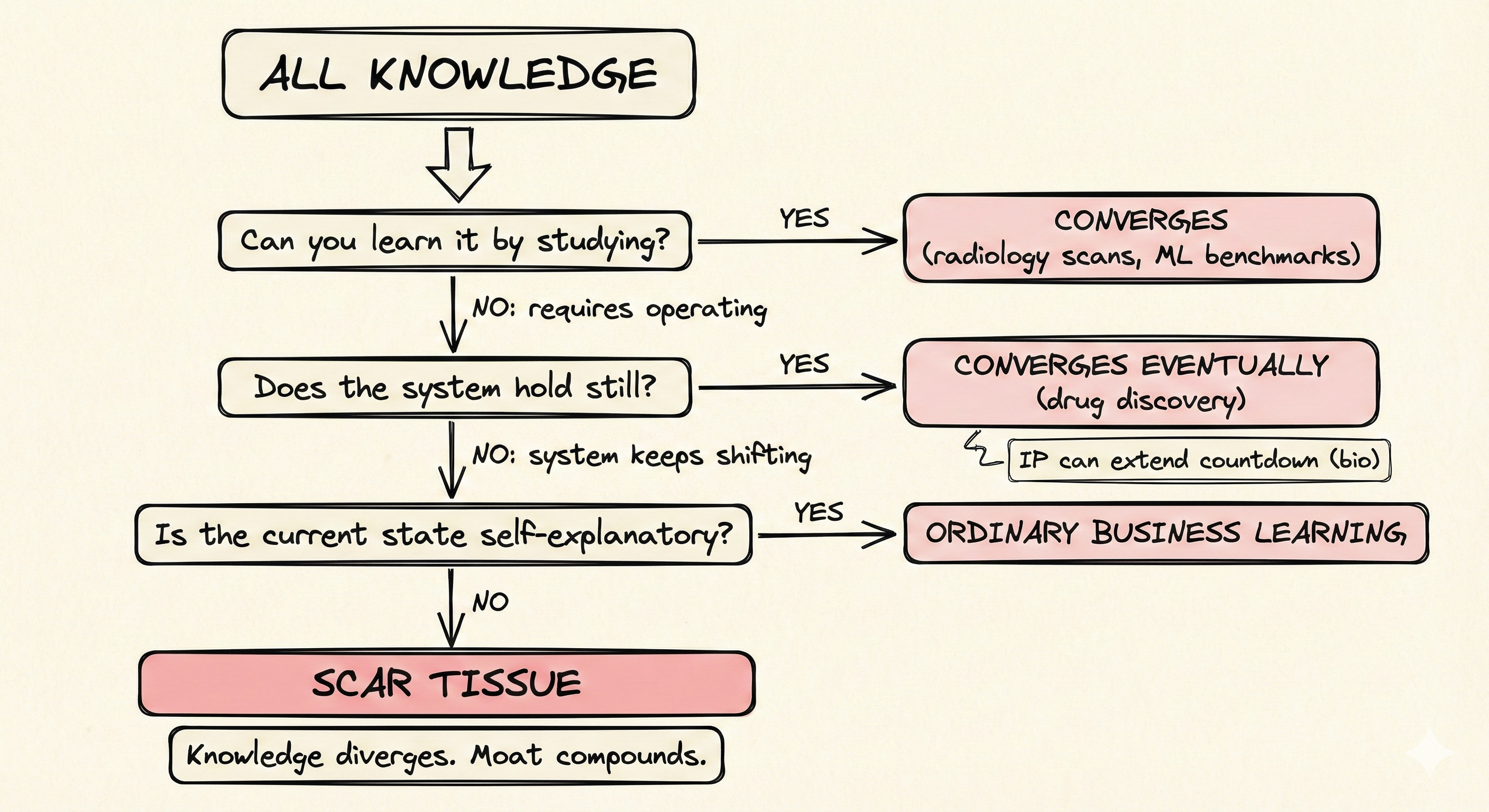

But not all knowledge is scar tissue. Most of what companies call "hard-won" turns out to be the kind anyone can learn from data. What kind of knowledge actually retains value when code is free?

Earned one surprise at a time

Consider two medical companies. One spent years collecting a million radiology scans, each labeled by expert physicians. The other processed a million insurance claims, each submission shaped by what the last denial taught them.

The radiology company has a stockpile. The images don't change between readings. A competitor with a different million scans reaches the same diagnostic accuracy, and AI trained on any sufficiently large dataset gets there too. The knowledge is in the data, and data can be studied by anyone.

The claims company has something different. Each denied claim taught them something specific about how that payer evaluates that procedure, knowledge that only exists because they submitted the claim and saw what happened. The next claim they submitted was shaped by the last denial. A competitor can't reconstruct that sequence by studying outcomes. They'd have to submit a million claims themselves, one at a time, each one teaching them what to try next.

Some knowledge converges from data. Collect enough and anyone reaches the same answer. Other knowledge can only be earned by acting in the system and seeing how it responds. AI can study anything, but it can't operate for you.

But even operational knowledge isn't automatically scar tissue. It depends on whether the system holds still.

A drug company screens thousands of molecules against a biological target, each experiment shaped by what the last one revealed about the target's binding behavior. That's operational knowledge. You can't study your way to knowing which compound works; you have to run the assay. But the underlying biology is settled. The same molecule hits the same receptor every time. A competitor testing the same compounds gets the same results. Given enough time and funding, they converge on the same answers.

When the knowledge converges, the race is speed and scale. Run more experiments, collect more data, get there first. That's a real advantage, but it's a countdown. Every day the gap narrows, because competitors running the same experiments reach the same answers. Software rarely gets even the protection of patents, which is why scar tissue is all that's left.

Now consider the claims company again. The payer that changed its reimbursement codes last quarter will interact with the coding standard that takes effect next quarter, and the company's adaptation to the first change will itself create new documentation failures when the second one hits. The system doesn't just change; each adaptation reshapes the surface the next change hits. A newcomer entering today doesn't face the same payer landscape the claims company navigated three years ago. They face a system shaped by thousands of prior submissions and policy responses, and they have no context for why it behaves the way it does.

When a system keeps shifting, operational knowledge doesn't converge. It diverges. Each year of operating teaches you things that make the next year's lessons richer, because you have the context to understand what new changes mean. A newcomer facing the same change draws different conclusions, because they don't have the history to interpret it. The information isn't in the change itself — it's in the change plus everything you already know. A veteran reads the same regulatory shift and extracts twenty implications; a newcomer extracts one. Not because the veteran is smarter, but because each prior surprise sharpened the filter through which this one passes.

Why can't the newcomer just study the current state and catch up? Because operating destroys information: your actions change the system, new events rewrite the meaning of old ones, and the dynamics of how things failed aren't preserved in any record. Think of it as a landscape with peaks. When the landscape is smooth — one obvious summit, like the optimal schema for a database — any climber reaches the top regardless of where they started. But when the landscape is rugged — many peaks, separated by valleys — where you start and which direction you walk determines which peak you reach. Operating in a shifting system makes the landscape more rugged over time, because each year of operating creates new features in the terrain. The veteran isn't just higher up a peak the newcomer could also climb. The veteran is on a peak the newcomer can't even see.

The test is simple: can a well-funded newcomer reach parity by studying the current state of the system? If yes, the knowledge converges and the moat is a countdown. If no, the knowledge diverges and the moat compounds.

What determines which? Coupling. In the claims company's world, everything touches everything — reimbursement codes interact with coding standards, coding standards interact with payer policies, payer policies reshape documentation requirements. Change one element and the change propagates through all the others. The system isn't being changed by an outside force. The connections between its parts are themselves the engine of change.

In the radiology company's world, nothing touches anything. One patient's scan is independent of every other. The same is true for most of what passes as "hard-won data": user preferences, behavioral patterns, training datasets. Each data point stands alone, unentangled. A newcomer collecting different data reaches the same conclusions, because independent observations produce convergent answers. The fault line between moats that compound and moats that erode is whether the parts of the system are coupled.

Scar tissue is operational knowledge earned in a coupled, shifting system where the current state isn't self-explanatory. It can't be studied, and it can't be rushed. But can it be simulated?

The speed of reality

This is where the last escape hatch closes.

If scar tissue is just knowledge earned over time, why not throw a thousand AI agents at the problem? Simulate every possible regulation, every bank failure, every edge case. Learn in days what took years.

You can't, because a simulation that actually works, one that responds to your actions the way reality does, adapting and surfacing new failure modes in response to your fixes, wouldn't be a simulation. It would be the system.

To simulate is to operate.

You can't learn from next year's regulation this year. The bottleneck isn't intelligence; it's time. The learning rate is set by the speed of the world, not the speed of the agent.

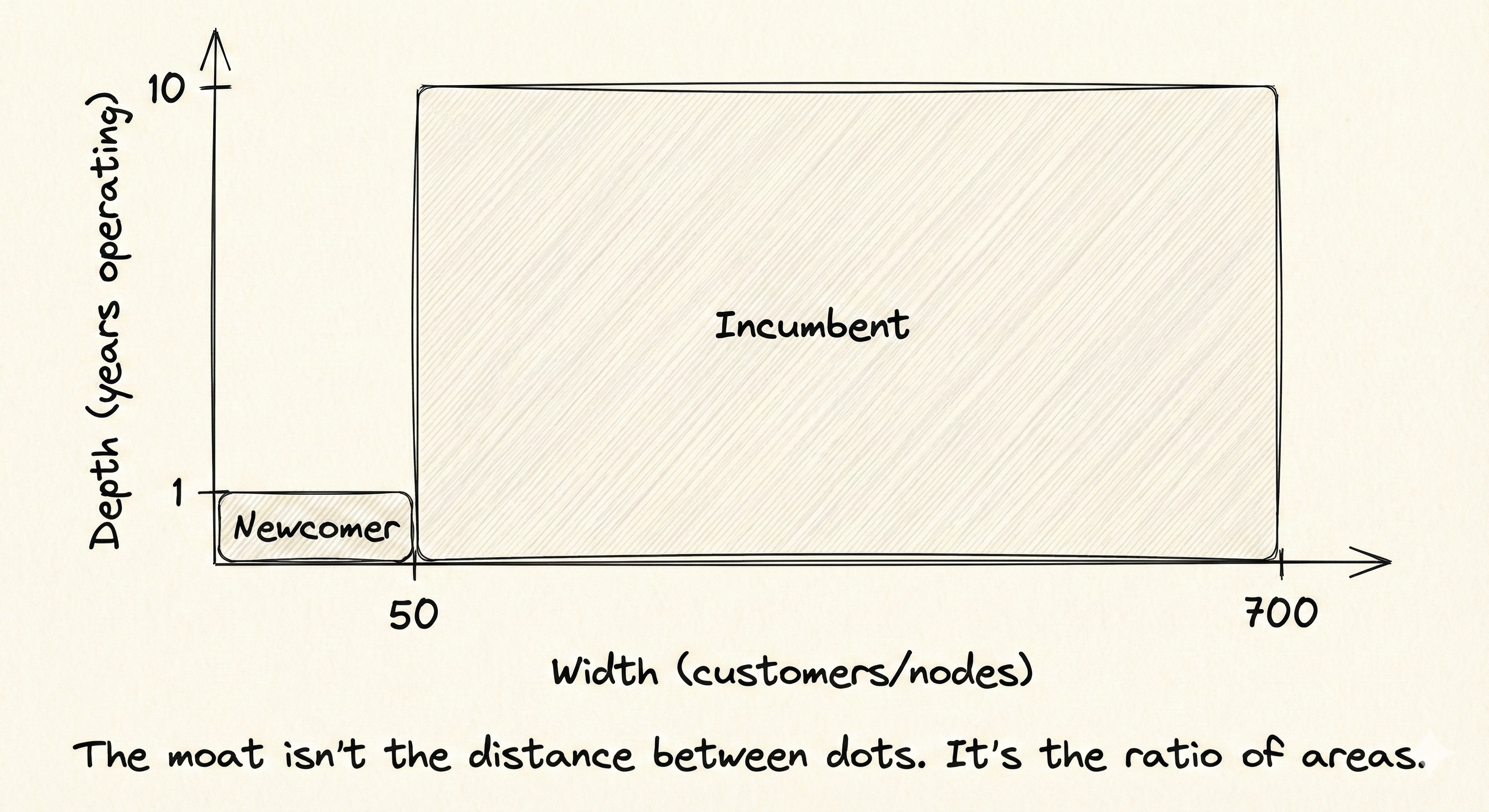

Consider Epic Systems, running clinical documentation across seven hundred hospitals. When a new billing code disrupts reimbursement in Houston, what Epic learns from that disruption reshapes documentation strategy at every other hospital processing the same code. Seven hundred hospitals probing the same coupled system — different payers, different state regulations, different patient populations — surface seven hundred different failure modes from a single regulatory change. And because the system is coupled, those failures don't just add up. They entangle. What one hospital reveals about a billing code reshapes what another hospital's denial means, producing insights neither could generate alone.

A newcomer with fifty hospitals doesn't just know less. They're missing the entanglement. Seven hundred hospitals produce nearly a quarter million pairwise interactions, things that only surface when one hospital's surprise illuminates another's. Fifty hospitals produce about twelve hundred. The gap isn't 14 to 1. It's 200 to 1.

The gap between those who have scar tissue and those who don't doesn't just persist. It widens. Each shift in the system generates surprise, but the same surprise contains different information depending on who experiences it. A richer history makes a sharper filter — the incumbent can distinguish between explanations a newcomer can't even formulate.

And it's not just width. It's depth. Each new regulatory change interacts with every previous one. When Brazil lowered the threshold for high-value transactions, a newcomer saw a parameter update. Stripe saw a cascade: which merchants would be reclassified, which settlement rules they'd collide with, which rerouting patterns from two years ago would prevent the freeze they'd already survived once. Same change, entirely different ability to act on it.

The moat compounds along two dimensions at once, width times depth, and each one grows faster than linearly.

The same knowledge gap creates two forces simultaneously. Customers can't safely build around it — the verification cost of discovering what you don't know, multiplied by the cost of being wrong, is what you pay the incumbent to avoid. And competitors can't quickly learn past it — the knowledge compounds faster than a newcomer can accumulate it, because each surprise teaches the incumbent more than it teaches someone without the context to interpret it.

What you pay for scar tissue is two things multiplied together:

Verification cost × cost of being wrong.

The more it costs to verify your own alternative in production, and the worse the consequences of failure, the more scar tissue is worth. This is why you pay Stripe despite being able to build payments in an afternoon. The code is free. The verification — actually processing transactions across jurisdictions until you've found every failure mode — is not. And you're not just paying for what they already know. You're paying for them to keep learning on your behalf, because staying current in a shifting system is ongoing work that compounds.

Critically, verification cost is dynamic. It increases over time. On day one, your AI-built payments tool passes every test you can think of. On day thirty, a new edge case appears. On day ninety, a regulatory change hits a flow you didn't know was affected. The gap between the verification cost you estimated at build time and the verification cost you actually face is proportional to the unspecifiable portion of the product. For products that are mostly specifiable, the gap is small — your AI-built document editor drops formatting, you notice, you fix it. For products with large unspecifiable layers, the gap is enormous — and by the time you discover it, the damage is done.

What AI actually changes

AI doesn't eliminate advantages. It clarifies which ones were real.

AI makes convergent learning nearly free. The entire loop of collecting user preferences, finding patterns, and improving the model accelerates equally for everyone. Whatever advantage you had from collecting data longer or at greater volume compresses toward zero. The playing field flattens not because the learning didn't matter, but because everyone can now do it just as fast.

But AI can't accelerate divergent learning. It can't generate the real-world surprises that produce scar tissue — it can't make regulators change their rules faster, cause attackers to adapt, or surface the specific ways a workflow breaks in production. These loops are bottlenecked by the speed of reality, not the speed of computation.

What AI does do is compress reaction time. When a new regulation hits, the company with scar tissue and AI can scan its entire history for affected patterns, draft compliance patches, and test them in hours instead of months. The surprise is the same for everyone. The reaction is not. AI agents operating in reality do let newcomers accumulate scar tissue faster — but the incumbent's AI acts on years of accumulated context, extracting more from each surprise. The newcomer's agent is walking the path. The incumbent's agent is running.

Post-AI, the gap between convergent and divergent learning widens. Every company's convergent advantages erode simultaneously, which makes their divergent advantages — however modest they seemed before — the only thing separating them from competitors who can build the same product in an afternoon.

One caveat. Scar tissue becomes worthless when the system it was earned in gets replaced entirely. Chegg had years of operational knowledge about how students study: which questions they struggle with, how to match explanations to learning patterns, which textbook solutions drive retention. All of it earned by operating. Then AI didn't just compete with Chegg — it replaced the system of "search for an answer, read an explanation, try again." The operational knowledge about human-mediated Q&A didn't transfer to a world where students ask an AI directly. The hardest judgment isn't whether your moat is real. It's whether the world is still shifting within the same system, or replacing it with a different one.

What's left to sell

Every company that bundled code with operational knowledge is splitting apart. The code goes to zero, and what's left is whatever scar tissue was inside it. The question for any bundled company, Salesforce or Workday or ServiceNow, is whether its operational knowledge survives independently when anyone can rebuild the product in a weekend.

This is why vertical AI is such fertile ground for moats. A vertical AI company picks a coupled system and operates inside it. Each customer becomes a probe at a different point of the system, each probe generates scar tissue, and because the system is coupled, each customer's surprises don't just accumulate — they entangle with every other's, reshaping what the whole network knows. Scar tissue protects against newcomers, not against other veterans who earned their own in adjacent territory — multiple companies can occupy different peaks on the same rugged landscape. But any newcomer trying to reach those peaks starts at the bottom.

Abridge automates clinical documentation across hundreds of hospitals. The transcription is a solved problem — what Abridge actually sells is everything it learned about how payers evaluate documentation, knowledge that compounds as each hospital's surprises illuminate every other's. The transcription is the container. The scar tissue is the product.

These aren't software products anymore. They're shared operational knowledge, packaged as services. And the customers stay not just because the product works, but because of their own experience of relying on it under stress. Trust earned when it mattered — the payment crisis Stripe resolved, the claim denial Abridge caught, the attack CrowdStrike stopped — is scar tissue that lives in the customer. It compounds: trust leads the customer to bring harder problems, harder problems generate deeper operational knowledge, deeper knowledge earns more trust. The company's scar tissue and the customer's trust form a double helix, each advance feeding the other.

For founders: pick a coupled system — where everything touches everything — and operate inside it. Accumulate scar tissue faster than anyone else.

The scarce resource was never the ability to build. It was always the knowledge that only comes from operating in reality and being surprised by the response.

Reality is your moat.